"In a way you do have to turn off your higher faculties to engage with a baby—who has intense use for your creativity and resourcefulness and problem-solving skills, but who is not interested in what interests you intellectually."

—Julie Phillips (Milk Art Journal)

Interview with Emily Kinni

Where Death Dies

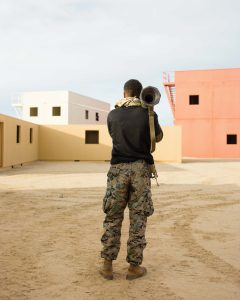

As of 2014, eighteen of the fifty United States have abolished the death penalty. But, beyond the abstract notion of justice, what has become of the physical locations where these punishments were administered? American photographer Emily Kinni has been researching the history of these former execution sites since 2011 and capturing the results in her series Where Death Dies. She spoke with GUP about researching sites that don’t exist anymore, repurposing sites of death into mundane spaces and the narratives of the people who keep history alive.

One of the most interesting aspects of the series that you’ve collected is that some of these former execution sites now host facilities not at all connected to penitentiary systems, like a mall, a residence or a highway. How did you go about the research of finding the exact location for these former execution sites?

I would first start with public archives and then, by meeting people who worked at these institutions, I would often hear of other people to contact. They may have been people who were, for example, related to a prison official, witnessed an execution as a child, or inherited archives that were stored in their homes. Then I would go to work to contact them.

I got very lucky to find such kind people with the time restraints I was working under. Typically, when I was allowed access into a correctional facility it was for only a very short window of time, so it was often stressful because I needed to quickly navigate getting a lot of information and capturing the images. Some states were simple, and some were more complicated. The sites of public hangings were especially difficult to access. In researching those specifics, I encountered challenges like changed street names or misplaced documents that described the account. Without the help of particular individuals I never would have narrowed the locations down, as they were really the only people to my knowledge with the answers I needed to locate these places. Without that generosity, the series wouldn’t exist.

Did you make any choices about which places to photograph based on what was standing there now?

The one choice I made when dealing with the issue of what is standing there now vs. what to show was in Wisconsin. Wisconsin’s last public hanging was reported at three different sites. I photographed all three, and based off my research chose to use the site that was most heavily documented (this is the house picture). I then met a historian who confirmed the house as the accurate site, so it ended up working perfectly.

It may be natural to think that a location that’s hosted executions would hold some innate emotional gravity, but most of the places you photographed look fairly innocuous. What was the experience actually like for you, being in these repurposed sites?

There’s no sweeping answer to this question. Instead I have fourteen answers, one for each site I’ve photographed so far. In short though, there were times that I was under extreme pressure to take the pictures as quickly as possible, and that was compounded by trying to remain collected enough to engage in essential dialogue with wardens and officers at the same time. There were moments I wasn’t sure I was going to leave with the material I wanted. Sometimes I was more focused on prison admittance and inmate interaction. Other times I was faced with needing to make a patch of grass, or a slab of concrete, commemorate a site of execution and make it into something interesting. Once I finally got access and photographed the sites, I mainly felt relief.

Did the sites convey any of the weight to you of being execution sites, then?

I couldn’t escape knowing and feeling the original purpose of the rooms, and the unavoidable tension of what the space had been, compared to what surrounded me. There was somehow a heavy weight attached to the transformation of a chamber into a janitorial break room or a vocational space for inmates. Not in the ways one might expect, though. It wasn’t about who was executed or why, the method administered, or the politics of those choices. It was about looking at how we deal with death by questioning the decisions made to mask the original purposes of these places. My concerns in no way argue with the morality of reuse, or criticize the officials responsible for these spaces currently, but questions what these decisions represent on a larger scale.

Was there any place that stood out to you in particular, for being something different than you expected?

They all held unexpected qualities. No one situation was really like the other. Personally, I am sensitive to the energy of interiors more than exteriors, so the interiors impacted me in a heavier way and had a lasting effect. I’m not sure why. I would usually re-experience being there after I’d had some time to reflect on what had happened when I was back in my car or motel room. In the moment, there was too much to juggle and consider.

More often than not I was faced with unexpected challenges, which often prevented me from finding the exact site and at the last moment someone showed me the way, or would present me with some form of evidence that would be fascinating. But in most situations something unorthodox and completely odd would occur. Sometimes it would scare me and other times just leave me bewildered and thankful.

Like what?

One of my favourite stories was in Wisconsin, the place where I photographed three different possibilities that were each the alleged site of execution, because I was having trouble tracking down which was correct. One of the only things I knew for sure was that the hanging was originally on a sandy knoll.

Wisconsin was maybe the fifth state I photographed. I had exhausted all of my research options after two days of digging through archives, and I was leaving the next day. I went to a tiny library branch outside Kenosha, the city where the last execution took place, though I knew they didn’t have what I was looking for. A helpful man at the library gave me the name of a local historian though, and told me, “If anyone knows the place where you’re looking for, it’s him.” At this point it was already around 6pm and I was leaving the next day at 2pm. I sat in my rental car and called him, but got no answer, and at that point I was pretty anxious that I would leave without enough evidence to know which was the correct execution site and have an accurate photo.

Thankfully, he called me back that evening and agreed to meet me the next day. He took me to the site of the hanging, which was someone’s house and a daycare parking lot. He referenced all of the research I had found, but he also knew the missing links. He had some documents in his home, which he showed me, though I had no idea how he acquired them.

There was a documented account from a child who had witnessed the execution and described the sandy knoll. He included the address of a home that then stood where the execution originally took place. By the time I found it, the street name had changed. So, I asked the historian how he knew this was the right site. He told me to get on my hands and knees.

This really startled me! But, then he got on his hands and knees as well, pointed to the ground and asked me what I saw. I said I saw cracked pavement. He said, “Look closer.”

There were ants on the ground, and he asked me what they were carrying. So, there I was on all fours in a parking lot next to someone’s home, with a man I had never met, looking at ants on the ground and I realized that they were carrying sand. They had paved over the sandy knoll. He started yelling with excitement and quoting some documents about the sandy knoll and why they paved over it.

That was a remarkable experience for me. I was so in awe of his passion about the subject. It wasn’t even about historical accuracy anymore, in a way; it was also about these people involved with the narrative.

What about the locations that still serve as corrective punishment facilities. You portray them from behind the barbed wire fences, which in a way doesn’t reveal the former mechanism of death but still admits the threat of loss of freedom. Do those places seem any more or less threatening to you knowing that they no longer killed people but could imprison them indefinitely?

The focus for me hasn’t been surrounding the morality of capital punishment, nor has it been the consequence or reward (depending on who you are talking to) of eliminating it and exclusively enforce life imprisonment or solitary confinement. Though I appreciate that this series invites that train of thought and the conversation attached to the multifaceted issue of the abolishment of the practice. I would rather hear your answer to this question than my own.

You’ve said that this is a work in progress, with four out of the eighteen states remaining, which have abolished capital punishment. What do you still hope to show with the project as you continue? Will the work be complete after those four additional states?

This work is at the mercy of the evolution of capital punishment and my hope is to continue to document future changes. I can only hope to continue build the series to reflect the choices being made in an effect to reuse or repurpose a former site.

This interview with Emily Kinni was published with GUP Magazine. We talk about researching sites that don’t exist anymore, repurposing sites of death into mundane spaces and the narratives of the people who keep history alive.