"In a way you do have to turn off your higher faculties to engage with a baby—who has intense use for your creativity and resourcefulness and problem-solving skills, but who is not interested in what interests you intellectually."

—Julie Phillips (Milk Art Journal)

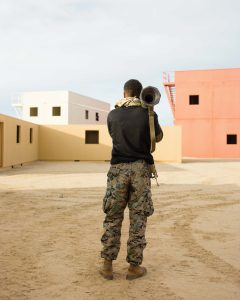

Interview with Karen Marshall

Between Girls

The transition from girlhood to womanhood is elusive by nature, something expressed best over time. New York based photographer Karen Marshall began documenting the daily life of a group of teenage girls in 1985 after she was introduced to Molly Brover, a junior at the Bronx High School of Science.Ten months later, Molly tragically died after being hit by a car while on vacation, but Marshall continued work on the project with those girls that she had met through Molly, up until the present year. In a beautifully longitudinal study showing three decades of female growth and relationships, Marshall’s series Between Girls is now on display in multimedia format, with images, audio, video, books, ephemera and more. We spoke with Marshall in this interview about documentary photography, emblematic relationships, and the difficulties of creating and maintaining a narrative over the long-term.

You began photographing this group of 16-year-old girls in 1985, when you yourself were in your twenties. What was your original idea behind the project?

I had spent ten years photographing on the street, doing environmental street portraits with medium format 2-1/4” (6×6), and by the mid ‘80s I had this great desire to, as I like call it, ‘move inside’. I mean it figuratively, but also to literally be off the street. I wasn’t interested in the street anymore, but I also was really interested in examining something that had more of a psychological idea behind it. Also just within my own transformation as a documentary photographer, I knew that you could talk about people and society and that it didn’t have to be about conflict – in fact I was really interested in the opposite. I wanted to look at emotional bonding, or those places where we find ourselves and our identity.

In retrospect, when I was coming of age in the 1970s, this was at the height of the women’s movement, and it was at a time of women’s consciousness raising, and so everything around me was based on that, in the media and in my own life. By 1985, nobody was talking about the women’s movement anymore, but there were two things that came to me: one was the question of who were the children now that are being raised by women who were part of that movement, and two, what is this about women and identity and youth?

If I looked at pictures in the US at the time, either I saw women under the poverty line, or I saw prom queens in the Midwest. I couldn’t find anything about women coming of age. Now of course there’s tons. But I decided that I wanted to look at urban teenagers, because that’s who I saw on the street at 3:00 in the afternoon, and I also wanted to look at middle class teenagers. I wanted to take out the poverty aspect, and I wanted to take out the uber-rich aspect, and talk about that middle-ground. Basically, I wanted to look at how I grew up.

Aside from the women’s movement that was a part of the culture of your youth, what was the significance of this passage from girlhood to womanhood for you personally?

I started to think about emblematic relationships, for example friendships that you have with people from your youth, that it doesn’t matter if you hardly ever talk to them or see them, but you know you could call them on the phone and within three minutes you would be back into a certain thing. That was something I was realizing was really important. And that the other thing was that, I started to realize that there was a language that women share with each other and oftentimes it’s really hard to describe. And so I thought, well, if it’s so hard to describe, then maybe photographs will really articulate it. So that was also part of it.

I certainly always had a lot of girlfriends, but it’s not like I was super girl-oriented or something. It’s just that I really knew that there were things about my identity, and things that were sacred to share with women that were somehow different.

This is an excerpt. The full interview with Karen Marshall can be read on GUP Magazine. We talk about documentary photography, emblematic relationships, and the difficulties of creating and maintaining a narrative over the long-term.