Julie Phillips: On Creativity, Motherhood and the Mind-Baby Problem

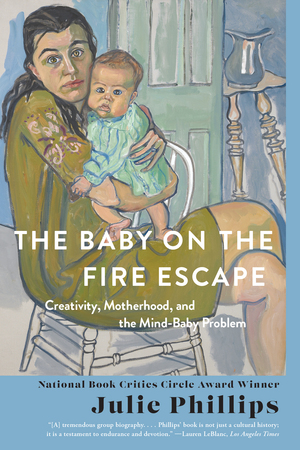

In her book The Baby on the Fire Escape: Creativity, Motherhood, and the Mind-Baby Problem, Amsterdam-based author Julie Phillips looks at the lives of an anomalous group of famous artists of the twentieth century—women who were both artists and mothers.

What she uncovers is a diversity of experience, with varying degrees of happiness and success.

The book covers artists and writers including Ursula K. Le Guin, Susan Sontag, Audre Lorde, Doris Lessing, Angela Carter and Alice Neel. In this interview, Julie discusses the pervasive judgment of mothering, how interruption makes itself felt on creativity, and the importance of being the main character in your own story.

Let’s talk first about this metaphor of “the baby on the fire escape.” What does it mean to you?

When I first did the book proposal, I realized that it needed a title. I scanned through what I’d written and there was that story about Alice Neel: Her in-laws, who were raising her child, had claimed that she’d left the baby on the fire escape to finish a painting—there wasn’t any evidence for that, it was just a sign of their judgment about her as a mother. When I thought about it, it seemed to me like a really good metaphor for a space that you try to achieve with your child: far enough out of mind that you’re getting your work done and close enough not to lose that bond of love and authentic connection that lets you enjoy your motherhood.

When it comes to the relationship of my writers and artists to their motherhood, I didn’t want to say of them that they were ‘good mothers’ or ‘bad mothers.’ There is already so much judgment around motherhood that I didn’t want to pile on more. Instead, I tried to approach it by asking: Did they enjoy it? Were they happy in their motherhood? Did it work for them? Did it put them in a better place emotionally? …Or not.

What is it about being an artist that is so difficult to combine with motherhood?

It isn’t just artistic work that’s hard to combine with parenthood. I’ve also had letters from scientists who see themselves in the stories in my book. Of course scientific work is creative, too, in its own way; it’s another form of making.

It seems to me that to write or create you need to be able to draw on yourself, the part of you that thinks its own thoughts and isn’t at the service of other people’s needs. Often that selfhood is equated with solitude. There’s this notion of the person fully devoted to their work, whether they’re alone in a room or alone wandering in the hills. I don’t think you have to be alone to work; you can share your physical and mental space with other people. But you do need to preserve the sense of selfhood, the wellspring from which you draw, of who you are and what you are bringing to the work.

That seems to refer to what you call in the subtitle the “mind-baby problem.”

Any kind of intellectual labor is seen as being canceled out by maternal labor. We associate the physical labor of motherhood with no mental engagement. In a way you do have to turn off your higher faculties to engage with a baby—who has intense use for your creativity and resourcefulness and problem-solving skills, but who is not interested in what interests you intellectually.

This is a preview/excerpt from an interview with Julie Phillips, published in Milk Art Journal, Vol. 1.