Alain de Botton: Art as Therapy

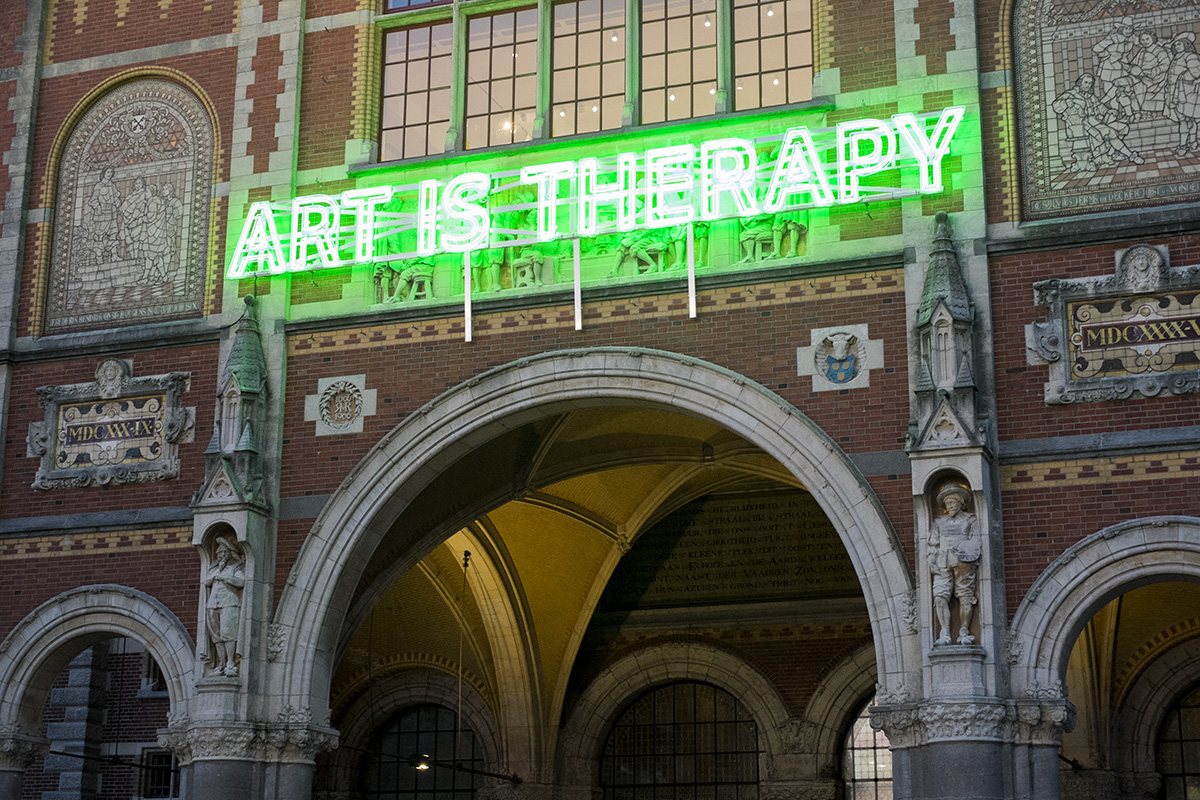

Philosopher and writer Alain de Botton has appeared twice, so far, on the TED stage, offering his approach for a more thoughtful way of living. His book Art As Therapy, co-authored with John Armstrong and released in late 2013, argues that museums have largely become lifeless tombs of intellectual study rather than sources of emotional consolation and connectivity. In response, the director of the Rijksmuseum offered de Botton and his organization, the School of Life, the opportunity to put theory into practice. Opening on April 25, 2014 the installation Art Is Therapy placed commentary-filled yellow square papers – colloquially called the post-its – throughout the Rijksmuseum. We had the chance to ask de Botton more about the installation and his theory.

Reactions to the Art Is Therapy installation have been alternatively empathetic and vitriolic. What do you suppose this divisive reaction says about the way people experience and value art?

The director of the Rijksmuseum said to me explicitly before the show: Alain, I will only consider this a success if half the people are delighted and half the people are appalled. Well, on this measure, we have succeeded, triumphed even! Some of the older art critics have been absolutely horrified. They have said: “What do you mean, art as therapy!” They have maintained that art has nothing to tell us directly about how we live and that it must never be used as a therapeutic tool. This would be to betray art’s function as a source of endless ambiguity, question and doubt. But I passionately disagree with this perspective.

For me, all culture – not just art, but also literature, philosophy history and so on – should be seen as a source of guidance and consolation. I have been practicing this idea since my book ‘How Proust Can Change Your Life’ 20 years ago – and I believe it to be true now today as well. I take heart from the fact that ordinary people have really liked the show – and have gone to see it in big numbers. What we have tried is something very new, very different and very unassuming. If anyone goes to the Rijks and has a new experience in front of works of art thanks to the show, I can be happy…

How might the ‘high art’ persona of the Rijksmuseum influence visitors’ willingness to participate in the idea of art as a means of therapy, as opposed to objects for historical study, cultural appreciation or intellectual pursuit?

When people want to praise art museums, they sometimes remark that they are our ‘new cathedrals’. This seems an extremely accurate analogy, because for hundreds of years, cathedrals were, just like museums, by far the most significant places in society; they were the buildings people lavished money on and felt proudest of. They were the spiritual hearts of the community.

But there remains a huge difference between museums and cathedrals in terms of our collective awareness of what the two types of buildings should be for. You used to go to the cathedral for some clear reasons: because you wanted to save your soul, because you were looking for comfort, you needed community, you wanted to develop your moral character or you were hoping for consolation and redemption. What do we go to the art museum for? We know that art is meant to be somehow good for us, but to ask simply ‘What is it for?’ may sound childishly naive, impatient or vulgar. Some of our visits therefore bear the hallmarks of an uncertainty about their purpose. There is huge respect but also, somewhere within many of us, a distinct confusion.

Now in truth, art can do for us a remarkable number of the very things that religion once did. Culture is in a position to replace many of the functions of scripture. Art too has the power to console us, it too can bring meaning and purpose, it too can increase our powers of empathy and generate a sense of community.

This is what the show at the Rijksmuseum is really all about. With a different ‘frame’ around them, art collections can begin to serve the needs of psychology as effectively as, for centuries, they served those of theology. Once curators put aside their deep-seated fears of a ‘purpose’ for art, works of art can be put to work on a therapeutic mission.

Is it possible to have a therapeutic or spiritual experience in an ornately painted, crowded room with guards?

You’re right, the museum is clearly not a perfect environment to enjoy the deeper meanings of the art it collects. It is like a filing cabinet which holds love letters. We are grateful to the cabinet, but we know the love letters were not made to be read or held in such circumstances. My only consolation is that now, mechanical means of reproduction mean that you can see the great masterpieces in exceptional detail on the computer screen and on postcards. People will say: it’s not the same – in the same way it’s not the same to listen to Bach’s Mass in BMinor on CD, but still, it’s not bad…

Do you think this curatorial method of artwork ‘recommendations’ based on emotional need could be applied also to books at your local bookshop or library or to a music store, for people who are seeking comfort but are feeling overwhelmed – or underwhelmed, as it were – by the art at hand?

Yes, my method is absolutely transferrable to other areas of culture, it doesn’t belong merely to art, it is something that you could practice with music, with cookery, with architecture… – and I am interested in all these areas, in many ways, just as much if not more so than art itself.

In the initial plans, it seemed that the School of Life would have the creative control to do a re-hanging of the museum, to reflect the argument that has been laid out in the book. How did the reality of logistics differ from theory?

The reality of logistics did force us to adjust the show a bit. We reorganised 6 rooms, but couldn’t transform the whole museum. Still, it has been a truly great honour – and a massive undertaking nevertheless. It’s by far the biggest single project I’ve ever done, and it has required months of time. The main problem was simply the sheer amount that had to be written: 200 captions takes a very long time, it was like writing a whole new book – but it was deeply enjoyable too. Most of the captions can now be found at: http://www.artastherapy.com/rijks

Were there any rooms or paintings in the installation that brought you particular or unexpected happiness?

Real happiness was to be found hanging out late at night with the wonderful curatorial people, laughing and thinking and being a community – in the presence of the great masterpieces of Dutch art. I have always been a great fan of the Netherlands, now this was a chance to live for a while in the country, work here and make friends. What a treat!

The artist Olafur Eliasson recently developed an app of art appreciation tutorials, one of which was based on ‘embracing uncertainty,’ where he says: “Putting particular interpretations – audio guides, wall text, press announcements and so on – limits our imagination when we encounter art. The critical potential of doubt disappears when always told what to do; your senses end up being dulled and numbed.” Given that there will always be tension between helping viewers along to understand art, and letting viewers experience it on their own – where do you personally draw the ideal line?

My view is that there is absolutely no danger of viewers having to follow the captions I offer them. If they don’t like them, they need only turn their head away. So the idea that I am coercing the viewer is madness, I am merely whispering into the ear of those who want to hear.

Also, I think Eliasson is overplaying the idea that the artist needs to always be a non-interventionist. What surrender! Why should art always be so silent, always be so meek in its desire to change the world…? I think it’s a disaster to leave it so that the only people trying to change existence are large corporations and bigoted polemical groups. It’s time for progressive causes to declare what they believe in too. There is no need always to be silent, in case someone is offended…

Is it now the case that “changes of existence” must be achieved institutionally, in order to compete with these large war ships of shouting noise, the corporations and polemical groups?

I’d love to say that the romantic vision of the artist or inspired person changing the world still works, but I don’t feel it does. Of course, one can have a wonderful impact on the inner consciousness of a few people and have a very nice life as a result – and this isn’t bad. But if really one is talking about changing the world, then it is only institutions that can do this, I sincerely believe.

Is there something more that museums can do to encourage curiosity rather than study?

They are doing so much. Most museums are now extremely committed to public education. But there is one thing they should do at once, and universally, and that is offer their collections online, royalty free, so everyone can use and see their images.

In the book, you write that the museum “contains a series of hints of how we might live, but ultimately it stands in relation to art, as school does to life – at a certain point we must go out into the world and learn to abandon our guides with the utmost respect and gratitude.” If we each have varying needs over the course of our lives, are museums inevitably limited by the nature of offering a static service for a dynamic need?

Museums are the place where the ideals of humanity are stored. Our point was that these storehouses shouldn’t merely be dead places which hold the past, they should be our guides to the future. Take Vermeer: the point of the Rijksmuseum should, in part, be to help Holland work out how it can live more in tune with the values of this great artist – in other words, not just preserve his work, but also preserve and spread the spirit of his work. That is the true mission of the museum.

Do you have any ambitions for further developing this idea?

I never abandon a project, everything is connected – and my work on art will feed into all other projects that I carry out. My feeling is that the overall mission of my life – to see if culture can be reconnected with the meaning of life – is not over yet, and there is plenty more to be done. I feel deeply privileged to have had the chance to work with one of the world’s great museums and to show – in action – what art can do for us.

How might the ‘high art’ persona of the Rijksmuseum influence visitors’ willingness to participate in the idea of art as a means of therapy, as opposed to objects for historical study, cultural appreciation or intellectual pursuit?

When people want to praise art museums, they sometimes remark that they are our ‘new cathedrals’. This seems an extremely accurate analogy, because for hundreds of years, cathedrals were, just like museums, by far the most significant places in society; they were the buildings people lavished money on and felt proudest of. They were the spiritual hearts of the community.

But there remains a huge difference between museums and cathedrals in terms of our collective awareness of what the two types of buildings should be for. You used to go to the cathedral for some clear reasons: because you wanted to save your soul, because you were looking for comfort, you needed community, you wanted to develop your moral character or you were hoping for consolation and redemption. What do we go to the art museum for? We know that art is meant to be somehow good for us, but to ask simply ‘What is it for?’ may sound childishly naive, impatient or vulgar. Some of our visits therefore bear the hallmarks of an uncertainty about their purpose. There is huge respect but also, somewhere within many of us, a distinct confusion.

Now in truth, art can do for us a remarkable number of the very things that religion once did. Culture is in a position to replace many of the functions of scripture. Art too has the power to console us, it too can bring meaning and purpose, it too can increase our powers of empathy and generate a sense of community.

This is what the show at the Rijksmuseum is really all about. With a different ‘frame’ around them, art collections can begin to serve the needs of psychology as effectively as, for centuries, they served those of theology. Once curators put aside their deep-seated fears of a ‘purpose’ for art, works of art can be put to work on a therapeutic mission.

Art as Therapy: A Discussion with Alain de Botton was originally published on the TEDxAmsterdam website. The installation Art Is Therapy can be viewed at the Rijksmuseum until September 7, 2014.