Come Hither: A Reframed Means of Seduction

What does seduction look like? How does a person communicate to another, unspoken, an invitation for intimacy? A fluctuation of the lips, a fire in the eyes, a curving of posture, a flourish of gesture… Through some nuanced combination of the cocktail components of our physicality we are able to create a visual package of information which, when decoded by the viewer, sparks desire.

But, far beyond that, how do we manage to photograph such a thing, so that it can be captured and re-visited, or shared to an audience broader than those present at the moment of production? Without a doubt, it’s a question that countless people have spent a lot of time investigating intensely with a camera.

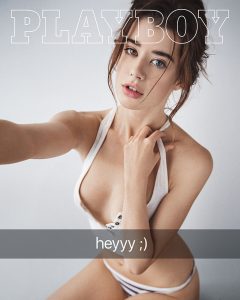

The visual language of seduction has certainly evolved over time. One of the clear landmarks on a winding road of meandering sexual tastes is Playboy’s recent strategic shift to stop featuring explicit nudity in the pages of its magazine. This act doesn’t so much signify that nudity is no longer desired, but rather, it acknowledges the current saturation point of nudity: no matter where you are on the internet, you’re never more than two degrees of clickable separation from some hardcore fucking and sucking. While some people will occupy themselves with seeking out ever-increasing extremities lockstep with their ever-increasing thresholds of arousal to achieve a dopamine high, others will seek out instead something subtler. The pervasive and continuous stream of availability of nudity, combined with the rising sense of isolation experienced by a modern life spent in front of a screen has created a new kind of fetish: the pursuit of intimacy.

Intimacy is often associated with sex, or sex acts, but it’s more accurate to consider it within the framework of emotions. It’s rooted in vulnerability, as when we suddenly perceive that we have established an unfiltered, or unmediated, connection to someone. While it was perhaps once the case that a photograph of a young woman naked in her dorm room was an expression of that vulnerability, and therefore achieved intimacy through the very nature of its printed nudity, that’s no longer the case. It’s titillating, to be sure, but it can no longer achieve the same emotional impact demanded by complex sexual needs that depend on more than mere arousal – it has to be able to generate desire, itself an emotional, rather than purely physical, state.

So, how can a photograph, lacking the potency of pheromones and other animalistic stimulants like touch and smell, manage to achieve anything approximating the same result?

What’s intriguing about Playboy’s cover choice, following their move away from explicit nudity, is its engagement with (or, capitalization on) selfie culture. It’s a shrewd, head-on commentary on an increasingly image-aware population. With the young girl holding her arm up like she’s taking her own picture (though, the photographer is Theo Wenner), and the text overlay flirtatiously beckoning, “heyyy ;)”, it’s almost as though Playboy is confronting their own obsolescence (ironically, or not) as the owners and purveyors of girls’ images. In one sense, it’s business as usual: a man has photographed a young girl provocatively. In another sense, the publication may have come to recognize that, in modern times, perhaps the most desirable woman is one who is in control over her own image.

And, of course, that conclusion has its own problems. Could we ever really reach an agreement on the ‘empowerment’ of women through selfies?

The truth is, there’s no truth when it comes to understanding each woman’s motivations for producing and sharing selfies. Whether a woman is cognizant of the image’s meaning and willfully participating in an act of measured control over the distribution of her image, or whether a woman is simply a mindless puppet participating in the patriarchy, whoring herself out for likes on the internet… we can’t say for sure, because we can never fully know the mind of another. It’s easy to pass judgment (isn’t that what the internet is for?) but it doesn’t make us any wiser.

These unanswerable questions are explored by American photographer Evan Baden (b. 1985, Saudi Arabia) in a provocative series he produced from 2008-2010, Technically Intimate. Baden sourced images from the internet, finding private moments on public ground, and then set about re-producing the scene of their creation using models. The resulting images are cleverly articulated, and technically well executed in ways that actual selfies seldom are, creating a distressingly sober look at the phenomenon of amateur image making. Showing views into the messy bedroom sets, and zoomed out far enough from the subject that we see the process behind the photo, the series finally gives us enough space to consider the complexity of the lives of the people who portray themselves. Behind that perfectly controlled pout, there’s something distressingly human at stake.

The selfie has come a long way. What used to require props like tripods and remote shutters is now something that can be performed at arm’s reach. What used to be passed from one hand to another is now distributed instantaneously, everywhere, with no physical limits to reproduction or simultaneous viewing. This creates a feedback loop, whereby one selfie informs others how a selfie ‘should’ look. As expert image-readers, we absorb and assess the value and success of certain images, and decide the way that we can best present ourselves, using an ever-evolving visual language combined with contemporary trends. We model and mimic, with occasional ‘inventions’ or re-interpretations of ideas and themes.

And, then, perhaps inevitably, after the trend is established, someone starts asking how they can make a buck off it. Pornography stole girls’ images from them to sell it off, only to have the efforts usurped by the groundswell of girls taking pictures of themselves, only to have the self-images they’d constructed once more appropriated, packaged and sold in a commercial product. The feedback loop of desire-making, image-making and profit-making continues.

I still do not know how to take Playboy’s cover, which seems in its careful construction far too manufactured to arrive at a genuine feeling of intimacy. The closest it can come is a simulacrum, which for me personally, only exacerbates the feeling of disconnection. But, who are we kidding, I’m not the magazine’s target audience, anyway.

In the factory that produces mass-appeal fantasies, however, the aesthetic of the selfie has for better or worse worked its way into the lexicon as a potent recipe for delivering the package of seduction. The selfie is our current lingo for expressing something private is taking place, something personal – even when it’s taken by another photographer.

Come Hither was published on GUP Magazine, looking at the rewritten rules for seduction in a photograph.