Interview with Juno Magazine

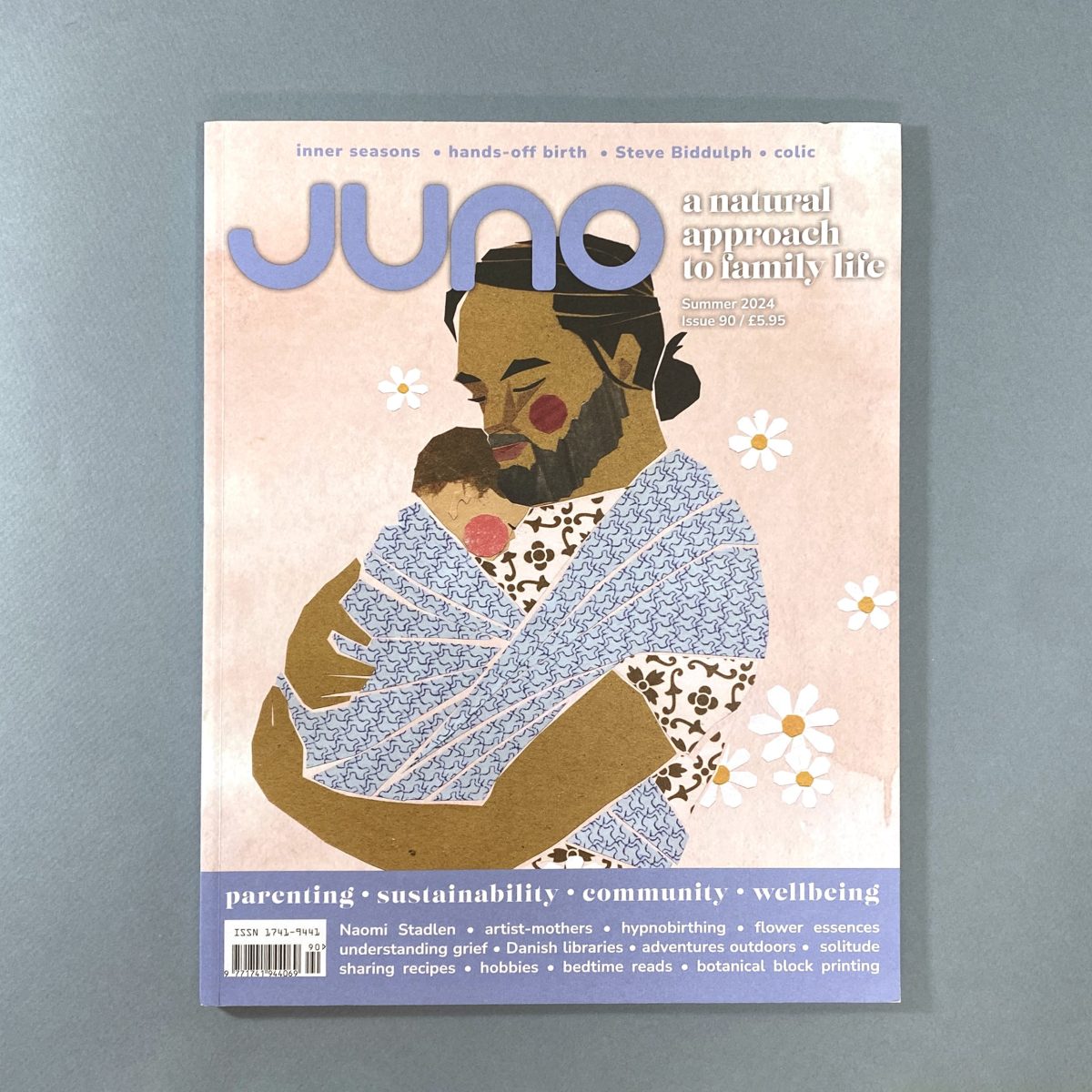

This interview with me, written by Alice Ellerby, was published in Juno Magazine issue #90, and is available online to read in full.

Katherine Oktober Matthews speaks to Alice Ellerby about her project Milk Art Journal, which delves into work by artist-mothers about motherhood…

“Motherhood in art is often otherised – somebody else speaking to a perception of motherhood – and because of that, it’s often about expectations rather than experience.” Milk Art Journal, edited by Katherine Oktober Matthews, explores artworks by artist-mothers about motherhood. Across three volumes, Milk presents a picture of motherhood from the inside, to challenge the centuries-old tendency in art to exclude the lived experience of mothers. Through candid and diverse expressions of motherhood, Milk offers “a better context of what motherhood actually is, and not just some context of idealisation”.

The three volumes are organised by theme, the first of which is Chores and Transcendence. When she began thinking about the project, Matthews explains that the idea of contradictions quickly emerged. “A lot of mothers might be commenting on the profound boredom and dissatisfaction of housework, but then how do you pair that against these little moments of awe that you experience in caring for children?”

The work included in Volume 1 is extraordinary (as it is across the journal). Sarah Lightman’s paintings illustrate the project’s aims beautifully. In one, ‘Madonna of the Soft Play – A Prayer for the Lost and Found’, the Virgin Mary, the archetypal perfect mother so often depicted in master paintings, finds herself deep in the ball pit. If there was ever an image to question the historical depiction of motherhood in art, surely this is it.

I love Tabitha Soren’s project too, Motherload. To create her photographic series, Soren “suspended a camera above her bed to capture the first three months of newborn life”, Matthews describes in the journal. She then layered the images over one another, “illustrating the haze of repetitive gestures and slight movements that comprise so much of postpartum life”.

Another of the featured projects, Pillars of Home by Csilla Klenyánszki, captures the way motherhood impacts the very act of creation. Confronted by the constraints of new motherhood, Klenyánszki challenged herself to construct and photograph her work in the time her son napped. She created impromptu assemblages from household objects, which seem to balance precariously. As Matthews writes in Milk, “The structures become makeshift answers to a common dilemma: ‘How does a mother find balance between all her priorities?’”

Intrigued by this question, I ask Matthews how the process of creation changes for women when they have children. “I think for a lot of the mothers that I spoke with it became something they tried to fit in wherever possible. Some artists have designated working time, but a lot don’t.” She gives Andi Gáldi Vinkó, interviewed in Volume 3, as an example. “Childcare is an issue for her,” Matthews says. “She doesn’t allow herself to pay for childcare when it’s just for her own speculative work. One of the things about artwork, of course, is that it’s frequently speculative, so it makes it harder maybe to justify spending money to create that work.”

So, I wonder, do artist-mothers feel they have to have ‘success’ before they can allow themselves to spend time and money making work? “I think that depends very much on when you give birth relative to your career,” Matthews says. “Some women have internalised that their work has value before they have children, and those are the ones who might keep pushing the hardest for that continued time to dedicate to their work.” She goes on, “To some extent, Andi Gáldi Vinkó had stopped seeing herself as an artist because she had been so up to her neck in caregiving, and had disconnected quite a bit from the art world. Some people burn with a little more urgency to make their work at any given moment, and some may feel it slipping away, and they either make more work in response or possibly they take a break, and that might be OK too.”

This was the case with ceramicist Marice Cumber who also features in Volume 3. She stopped making art when she had children, and after a gap of thirty years, returned to her creative practice. Her work now is a reaction to having spent the preceding decades raising children instead of making art. Matthews describes Cumber’s series, The Struggle Is Mine, in Milk:

Handmade from stoneware clay, the cups achieve a purposeful awkwardness in form, and are colourfully decorated with glib words of affirmation and confessions. Her messages combine confidence and doubt, strength and vulnerability, sadness and hope. Through her work, she’s able to reflect on the life that she lived in absence of an ability to create. Ultimately, Cumber’s work speaks to the long journey of self-understanding and acceptance.

Many of us grapple with the huge life changes brought by the transition to motherhood and each of us responds in our own way. Some of the decisions we make feel like sacrifice, others like stepping into ourselves. Of the various choices made by the artist-mothers she spoke to, Matthews reflects on the value of each path taken: “I’m very enamoured with all of these different expressions, no matter what stage of life or motherhood.”

I ask Matthews whether her own work changed when she became a mother. “Without a doubt,” she says. “Quite a lot of my work has always been reading and research and investigations and that is a lot more slow now. To maintain prolonged attention and focus, especially for research, that’s a challenge. There are some tasks that I can do in short spurts – sending emails and the administration side of work – then there’s the deep research tasks, and I’ll do that on a day when I’ve got a concentrated block of time. I’m figuring it out still; it’s an evolving picture.”

The challenges of organising work while caring for children will be familiar to many. I ask whether Matthews witnessed a change for artist-mothers as their children got older. “Absolutely,” she says. “In the artists who are included in Milk, there are some with young children and some who are already empty nesters, and each stage of parenthood has its own gifts and challenges.” She cites Julie Phillips, author of The Baby on the Fire Escape: Creativity, Motherhood, and the Mind-Baby Problem, in which she looks at the lives of famous artists of the twentieth century – women who were both artists and mothers. For an interview in Volume 1, Matthews and Phillips spoke about the challenge of the empty nest. Matthews recalls, “Yet, even before then, she felt challenged when her children were a little bit on the older side – say, 8 – and they stopped physically needing her so much. Those are all transitions, and they give more space for work, perhaps, but I don’t think that children ever stop interrupting you – they never stop being on the other side of the bathroom door, needing or wanting something. But the evolution of parenthood offers different sources of inspiration, and each stage can present you with new opportunities.”

The work included in Milk depicts motherhood in a way that feels simultaneously familiar and radical. I’m curious as to why the journal feels so bold when, to any mother, the ideas it grapples with are so relatable. Why haven’t we seen more of this kind of work before? I ask Matthews whether motherhood is stigmatised in the art world. “I think it must be by nature of the fact that so many artists don’t speak openly about it,” she says. “There is, I think, a growing community of women who, once they are mothers, will speak to other mothers about it, but in the context of dealing with galleries or venues or publishers, you might just quietly never mention it.” Milk is part of a “growing movement of visibility”, which Matthews hopes will correct this. At the same time, she understands why it might be something that people don’t voice, and points to the “reality in the numbers and statistics that show that women in general are still not represented in museums and galleries, and mothers are an even smaller subset of that”.

Milk robustly disavows the notion that lingers in corners of the artworld that you can’t be an artist and a mother. “There are so many artist-mothers making work,” Matthews says. “It does become challenging, and it might change your work, but it is absolutely and completely possible. Your path will look a little different, but that itself is the norm. There is no one way to carve a path.”

This is just as true of motherhood as it is of art making. Matthews’ project offers a more rounded view of motherhood than the art world has historically presented. “It’s been an incomplete picture,” Matthews says. “For the wellbeing of mothers, it helps to see these other views because there’s already so much self-judgement and shame and feelings of insecurity arising out of idealised notions of what a good mother is. To see these lived experiences offers more space to the vulnerability at stake in motherhood. One can aspire for oneself, but it doesn’t have to be a yard stick we measure ourselves against in order to feel at ease and good in our parenting.”