On Immortality

I mean, they say you die twice. One time when you stop breathing and a second time, a bit later on, when somebody says your name for the last time.” -Banksy.

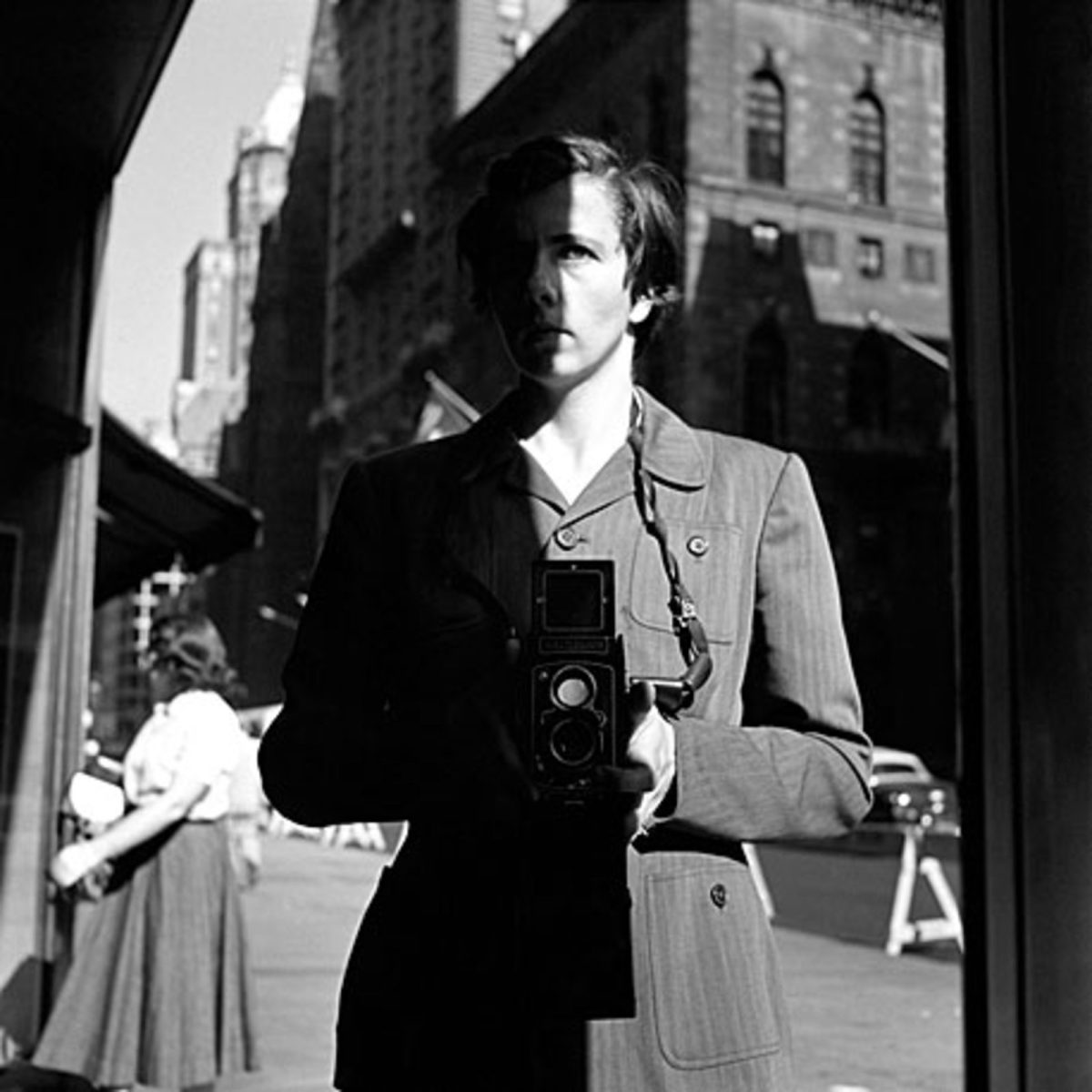

The sudden emergence of the photographic works of Vivian Maier onto the global stage of the art world is an interesting phenomenon, leaving in its wake many questions about the nature of art, the practice of photography, and our ideas on immortality.

Vivian Maier was, for all intents and purposes, an unknown individual, who lived and died without major event. She worked as a nanny, taking photographs in her spare time, though did not show her work to anybody. After she died, a storage closet with 100,000 negatives taken over her lifetime was discovered, and brought to the public eye with great fanfare, inclusive of worldwide exhibitions and a book release. The promotion of the work heralded her as a great unknown, a master photographer who was never recognized, even an enigma of a person. But what’s really there, aside from the PR?

Photography has often been recognized as a medium of creating physical memories. It provides evidence of existence, of both the photographer and the photographer’s subject. In this way, it fulfills the basic function of many of man’s creative efforts: one’s name carved in stone, so it can last past the body’s decay. It is the need of humanity to give proof and validation of one’s life, to seek immortality.

All people struggle with the concept of death; it’s the cost of mortality. Many are comforted by the idea of being remembered; the idea that they can be thought of fondly, written of, or sit on the tips of people’s tongues, even long after they’re gone. Our entire waking lives, we can only know the contents of our own minds, our own bodies. We can never be certain of our existence, of our place in the world, until we see it reflected by others.

It is through Vivian Maier’s body of work that we resurrect her. We see her work, we talk about it, we say her name again, and she lives.

A lifetime of photographs is an amazing find. We can almost feel that we know this woman by being able to see the world through her eyes.

In the future, following a generation of ubiquitous cameras and unlimited digital space, it’s likely that a posthumous treasure trove like this won’t impress us. Having photographic records are the rule now, not the exception. 100,000 images won’t even seem like a lot. Perhaps it does feel more real to us, that Maier produced physical slides; we can feel that we really have discovered buried treasure. On the other hand, to discover just as many digital photos that could be deleted by a simple keystroke, rendering mortality even to a life’s work, gives a state of impermanence that may be difficult to comprehend. What will be left of us — what are we at all — aside from our presence on machines?

Many of us photographers may feel that, were someone to probe through a lifetime of our work after death, we too might be heralded as unknown masters. Possibly it’s true. It may depend on who that ‘someone’ is. The case of Vivian Maier does indeed show that it matters who is the one ultimately responsible for your life’s work when you’re not there anymore. Had it been family or friends, it might have ended up in someone’s attic instead; more family memorabilia to sort through some day. Had the discovery been by someone with no interest in art or no sense of what could be done with the photos, it might have ended up in the trash.

In those cases, we would not be talking about Vivian Maier, and she might still be dead, instead of resurrected.

Ultimately, when I look at the body of work produced by Vivian Maier, I do see what they tell me is there: a great street photographer who gives us another look into history, giving us a taste of what it was like to be in a certain place at a certain time. But I also see what it could just as easily have been, what we all could just as easily be, and what we’re all fighting to save ourselves from becoming: dust.

On Immortality was published online at GUP Magazine.