"In a way you do have to turn off your higher faculties to engage with a baby—who has intense use for your creativity and resourcefulness and problem-solving skills, but who is not interested in what interests you intellectually."

—Julie Phillips (Milk Art Journal)

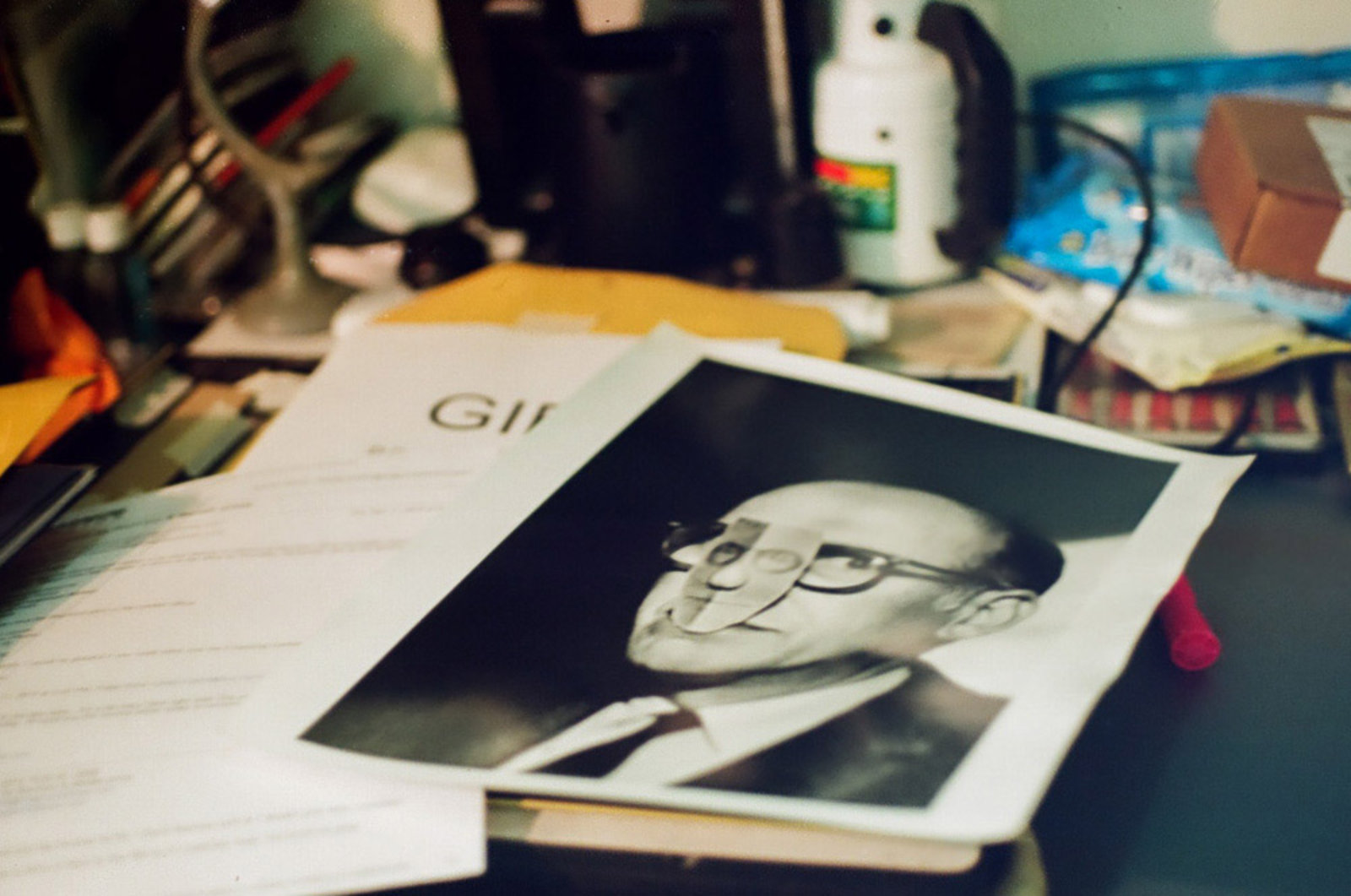

Interview with Pablo Inirio

Keep it Simple

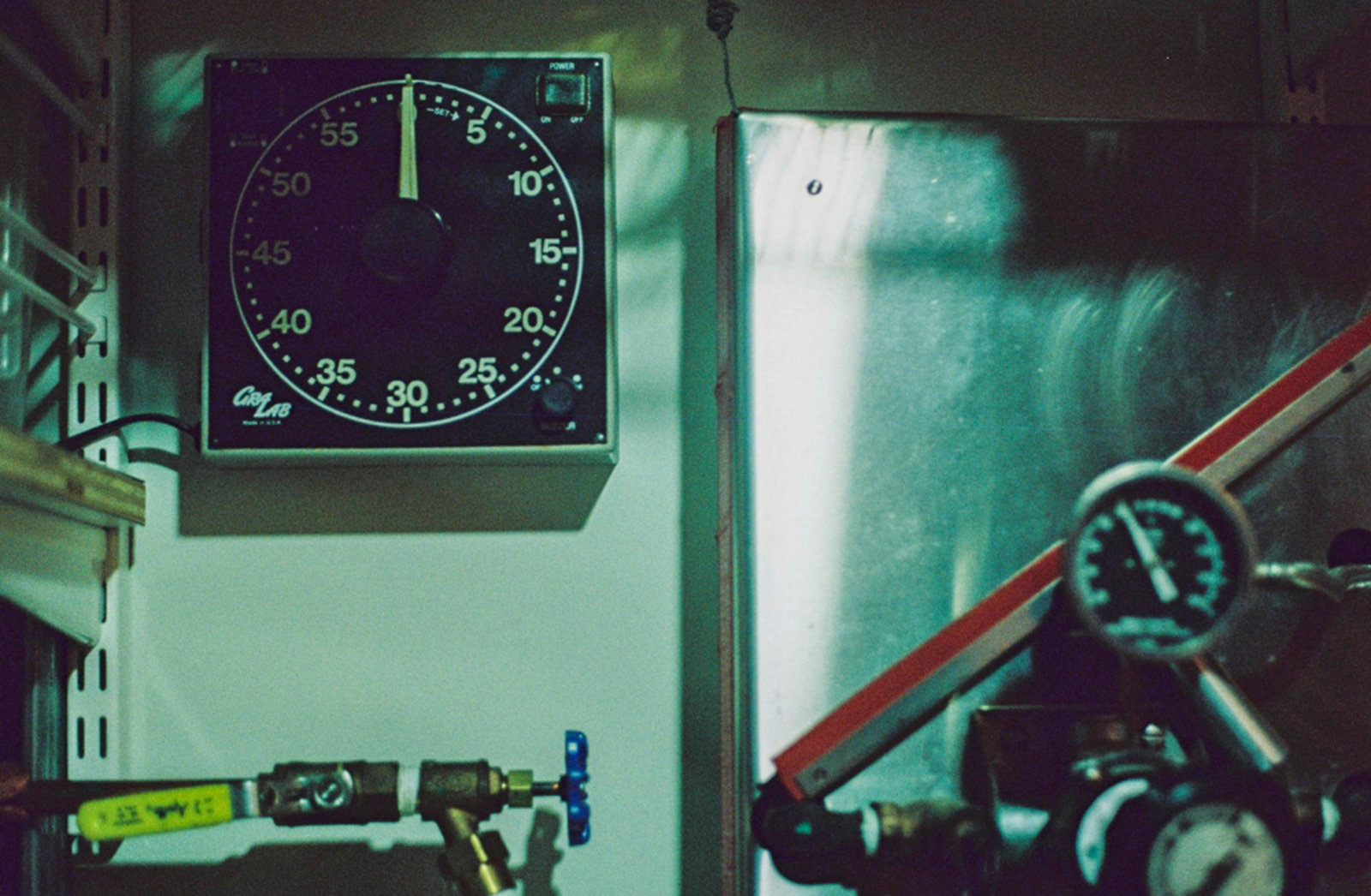

Pablo Inirio is a master darkroom printer for the prestigious Magnum photo agency, charged with the responsibility of making prints of some of the most iconic black and white images in history. In a world of increasingly few professional darkroom printers, the skills he hones seem today almost like a dark art, both chemically scientific and enigmatically magical. We paid a visit to the Magnum office in New York City to talk with Inirio about the printmaking craft of modern times.

Tell us what it means to be a darkroom printer these days: to what extent is it based in craftsmanship or art or science?

A lot of it is just craftsmanship. You can’t really get so much into the art, because it’s not your picture. When it’s someone else’s thing, I have to keep a neutral feel. I have to just print it how they want it – and that’s fine! It actually makes life easier, because if you have total freedom, there’s too much range. This way, you get a negative, you give it some good shadow detail, some good highlights—and boom, it’s done. If I know the photographer’s looking for a certain look, then I do it, but most of the time they don’t say anything. They just say, “Here, print it.”

As far as science, it’s pretty straightforward. If you know how to mix the chemistry, you’re fine. I don’t do anything fancy, I keep it really simple in there. Basic developer, like Dektol, you got your stop bath, a basic rapid fixer, like a non-hardener, wash, sepia tone. Nothing fancy. I don’t have time to do anything fancy. It just has to wash really well, tone it nicely, then wash it again, and it should last for years and years.

Do you ever disagree with a photographer about how to print a photo?

I like when the photographer’s arguing with me about a print. I argue right back! I try my best to convince them to my way but in the end it is their picture, so I have to do with they want. They went to the Amazon to shoot that picture—you didn’t—so you don’t have a say.

When you’re printing for someone you have to leave your ego out of it. They know what it looked like, and you hope that they remember the feeling they had. What I end up doing a lot of times is I do it their way, and I also give them my way, so they can choose.

You produce a lot of prints for photographers who are no longer alive, though. How do you print when they’re no longer around to argue with you?

I do a lot of estate prints, yeah. Luckily, I was around when they were around, so a lot of the pictures I’m doing now, I worked with them before. So I’m trying to keep in my mind the same look that they liked then. I have to respect what they wanted. But most of the time, I gotta tell you, they just let me print it, you know? No one really interfered much—or it wasn’t so much interference but more like, they trusted you, I guess.

How much time would you spend on a typical print, from the time you take out the negative to a finished print?

Let’s say an hour and a half to two hours to make it really nice. I don’t rush in there much. I put on the music, I got the mood lighting going, the water’s running… it’s a zen kind of a thing. You can’t rush your judgment too much, so you might go have some coffee, come back and look at it again, figure out what it needs and then you do the print. If it’s a tough print, and there are some areas that have to be lightened, and there’s no other way to do it, you have to make a mask. In Photoshop, you just make a mask in layers. Here you’re actually cutting out pieces of paper and you’re putting it on a piece of see-through plastic and you’re holding it over the print. All that stuff takes time.

I don’t want it going out of the darkroom unless I’m happy with it, you know? I don’t want to give people work that’s not up to my standards, and my standards are high. I’m tough on myself, I think I overdo it.

What are the types of things that make a negative challenging to print?

I’d rather have a negative that’s over-exposed than under-exposed. Under-exposed is hard because you want to bring out as much detail as you can—if you feel it’s necessary to the picture—and that’s hard to do without going grey. So when that happens, you end up working on a higher-grade paper with more black and white, which means less grey but you lose in the highlights, or you have to spend a lot more time printing for the highlights. So that’s hard. Whereas if it’s overexposed, I can always just add more time.

Is there something that makes a negative really fun to work with?

Yeah, when it’s a perfect neg, which I’ve never run into! (laughs) No, actually, some of the photographers are really good about exposure. I’ll give you an example, Chien-Chi Chang is awesome with his exposures. He’s so detailed about it. It’s a pleasure to print his stuff. Great shadow detail, great highlight detail… you can’t ask for more. His stuff is pretty straightforward—actually no, that’s a lie, it’s not straightforward, but at least I know the information is there if I need it. It’s not gone. It depends on the image, but generally his stuff is really nicely exposed. And he uses a lot of 2-1/4” (6×6), which is nice and sharp.

Considering you’ve worked on so many iconic images over the years, do you have a favourite print of all time that you’ve done?

I’ve printed the James Dean in Times Square a bunch of times. Like a lot of times. It’s not an easy print! He’s a little bit under-exposed, and you want to have just enough information so he’s still kind of moody. Even though it’s kind of a rainy, cloudy day, the sky is kind of overexposed a little bit, so you kind of have to bring that down, you want to keep the contrast snappy… so it’s an interesting print to do! I have my notes and I follow them as much as I can, but it changes from day to day; I can do it one way one day, and the next day, for some reason, totally different. I like that print a lot.

I have pictures in my mind that I know I love the picture, but I’m trying to remember if they’re hard to print or not… (laughs)

You’re actually working as a freelancer now. How is the market for work these days?

The demand is pretty steady. It has its ups and downs: you’re crazy busy one month and the next month you’re wondering why you’re here. But it always seems to rebound and there doesn’t seem to be a pattern. It’s kind of like playing the stock market, so if you don’t have the stomach for it, don’t do freelance! You’ll go crazy.

But I don’t know how long this will last, being realistic about it. There aren’t that many labs, here in the NYC area anyway, that do this. Everybody’s doing digital and I can’t blame them. It’s a lot easier, I think it’s more profitable. But I still like doing fibre, I like the feel of it, you know. I can’t say I like the smell of it, but I like the feel of it. The magic is still there. So I’ll keep doing it as long as they want me to do it.

Do you also learn digital printing on the side?

Yeah, yeah, sure! You can’t stay in a cave, you know… (laughs) You have to go out and see the grass. It’s a whole other world out there. I know how to do Photoshop and stuff, but I’m not really well-versed in it. You have to keep on top of what’s happening out there, you know.

And it’s exciting, because it made photography accessible to so many more people. Look how many things we find out about now, like with law enforcement, things that you would never see – now we got film of things happening! You know, I think it’s really good. And also, just on the aesthetic sense, if you have a camera with you all the time, which basically everyone does, if you see something that interests you visually, you photograph it! I think that’s really good, it opens up people’s minds to exploring creativity.

Of course now, everybody thinks they’re a photographer. Still, people should train. Learn the principles of what makes a good photograph. Ask yourself: why does this photograph look better to me than that one? And learn why! The certain way that the mind works, and you know it’s just natural for us to like a certain pattern rather than another pattern. You should know why, that way you can do better pictures or more appealing pictures.

How has printing changed over time, since you got started?

When I first started in high school – that was so long ago! – there was such a variety of paper available, so many manufacturers. You could have a choice of ten different paper surfaces from the same manufacturer: you could have silk, you could have perfectly glossy and smooth, you could have totally matte. The papers came in different tones, you know? I loved this one paper that was made by Agfa, called Portriga, I don’t think they make it anymore—It’s gone! It had a weird sort of yellowish-green look to it, but it already had a tone in it, which was really nice. We did a few experiments with lith paper, too, which was very high contrast paper that had a whole look all its own… it was amazing. I’m just thinking back to all these different studios I used to work with, and everybody had their own way of printing.

Is that one of the major technical challenges now, just the limitation of materials?

Yeah. I mean, what’s happening now is that you’re getting different surfaces in the digital world that you can work with. So, whatever we lost in the traditional printing world, now we’re gaining in the digital world. So it’s kind of interesting. And with a computer you can change the tone on screen, you can do split-toning on screen, whereas in the darkroom you would’ve had to do it with these toxic chemicals and stuff. It was horrible! I don’t want to look at it through rose-coloured glasses. It was toxic, it was horrible stuff, it stank. It smelled bad, like sulphur. But at the same time it was a lot of fun, so I kind of miss that. But to be honest I don’t have time to do any of that stuff anymore anyway.

Not too long ago I was doing some sepia tone tests. And the thing is, you have to hunt on eBay for the old Kodak sepia toners. You know, people had them in stock and now they’re selling them on eBay, cause you can’t get them anymore. But the thing is, the combinations that the photographers had, with the toner and the paper, you can’t get anymore, cause you can’t get that paper anymore. So now you have to experiment with all new kinds of paper. It was tough going, I tell you, trying to get the right tone we wanted. We couldn’t do it. In the end we decided to forget it.

Right now, trying to find that right combination… it has to do with temperature, it has to do with how much you dilute something, you put it in the bleach for so long, then you put it in the toner for so long… You have to have time to experiment like that. Literally you would need a week for something like that, and also keep really incredibly detailed notes about everything, every step of the way, what temperature this was, what temperature that was. But we didn’t have that time, we had maybe three days at the most, so it just didn’t work out.

The way you talk about this, it makes me re-think what you said earlier about the science being straightforward…

Yeah. We tried different additives, but again, the paper is so different now than what it was before. The paper had such a high silver content, and the look was different. If I look back at prints that I made maybe twenty years ago, and I took the same image to print it now, I’m trying to get it to what it looked like before, but it’s probably not the same, if you look at it really close. I can tell it’s not the same. I know you’re losing some bit of it. But I guess that’s where the craft comes in: you try to bring it back into the image. You can call it art if you want, but it’s more like craft. It’s art if it’s your stuff, it’s craft if you’re working for someone else—that’s the way I look at it.

Is there anything that analogue printing has gained over time? Something that makes you say “I’m glad we have this now”?

No. Not really, no. (laughs) No. We lost a lot. If you go to a store now, there’ll be a darkroom section, but every time I go it just gets smaller and smaller and smaller. You have to order. You can still find stuff, but you have to order it now, and it takes time. The problem is you don’t know when you’re going to need stuff. Half of the stuff I have to order, we have to wait 2-3 weeks, and you can’t wait that long!

And now with this attention from Homeland Security, you actually can’t order some of the stuff through the mail. You’d have to go to Pennsylvania or whatever to pick up 4 ounces of a chemical.

You can go online now which is a great thing – online is great. Online I can find different formulas that people have used in the past, and I can see if I can order those raw chemicals and then I can mix my own, but again, I would only do that for like a special project if something was necessary. Day to day, I just keep it simple. Basic developer, stop bath, fix, toning, washing… I just keep it very simple. Tried and true.

This interview with Magnum darkroom printer Pablo Inirio was published on GUP Magazine. We talk about the printmaking craft of modern times.