"In a way you do have to turn off your higher faculties to engage with a baby—who has intense use for your creativity and resourcefulness and problem-solving skills, but who is not interested in what interests you intellectually."

—Julie Phillips (Milk Art Journal)

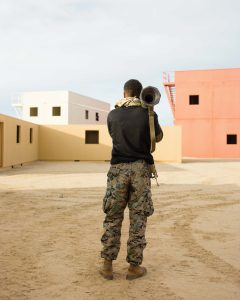

Interview with Álvaro Laiz

Hunting Among Equals

In 1997, a Russian poacher called Markov came upon the trail of a gigantic Amur tiger. Seeing the tiger’s footprints as a promise for a better life, Markov shot the tiger, but was unsuccessful in killing it. Over the next 72 hours, the animal tracked Markov down and killed him. Later investigations suggest that the tiger planned its movements with a rare mix of strategy, instinct and, most importantly, with a chilling clarity of purpose: the pursuit of revenge.

Inspired by this story, Spanish photographer Álvaro Laiz (1981) travelled to the remote taiga of the Russian Far East, where animism is a part of both culture and daily life. He speaks with us in this interview about living in severe isolation, silent hunters and co-existing with predators.

This project, The Hunt, but also your previous projects Transmongolian and Wonderland, builds on your interest in animism and shamanism. What is it that attracts you to these belief systems?

Well, I’ll try to answer that question briefly, because I could speak about it for hours. When I show these photographs to people, they tend to think this is part of our past. And that’s true, but I tend to think that it could be also part of our future, a kind of post-industrial society.

I try to learn about things that make me feel curious, especially because there is little information about those topics. I have talked to so many people – even in Russia they don’t know about the Udege and the tigers. I mean, they think Siberia is the end of everything, and the Primorsky Krai is kind of a mix of Chinese people and bandits, you know? Kind of ‘Far East’. So I try to experience them for myself. It’s not easy for me, coming from Spain or even from Europe, to find these kind of things. Usually you have to travel long distances to find folkloric behaviours like this. I don’t mean dressing like shamans and dancing and that kind of thing, but the people who live in nature and understand the way that things are done in there.

How isolated is it there in actuality? It may be easy to get some impression of being in the middle of nowhere, because your photos show these vast fields of snow and forest and nothingness, but is it actually so isolated?

Absolutely isolated. If you get killed in the taiga, no one will notice because you are isolated and no one cares about you. Last year, a Russian tourist who went there got killed – I don’t know why. Maybe they got drunk. They found him this spring. Some guy just found him in the middle of the taiga.

Who did it? Who knows. Why? Who knows. Things happen all the time. I mean it’s really easy to hide a corpse over there, so you better come with other people. And it’s also easy to get yourself in trouble because people really drink so, so, so, so hard.

Tell me about the tigers. What’s their relationship with the people who live there?

There used to be a balanced relationship. The natives from there, the Udege people, tend to consider the tiger the spirit of the forest. Of course they do not think that anymore, at least not all of them. They respect the tigers and will say, “Okay, I won’t touch her” – they usually refer to tigers as ‘her’. They try to stay equal with the tiger.

After Perestroika, it’s kind of, I could say, a ‘medieval society’, where only rich people are allowed to hunt, because you have to pay so much money for hunting rights and for the right to have guns and all of this. And some people come into the Primorsky, and they don’t respect the rules, they just come and try to hunt whatever moves.

So, we could say there are two different approaches to the tiger: one is the Udege way of life, where they try to live there and be equal with the tiger, the taiga and everything, because they depend on the tiger. And, the other one is a touristic, rich-person. They go there with modern equipment, modern weapons and so on, and they just hunt for fun.

You said the Udege depend on the tiger. In what way?

For example, if the tiger disappears, there will be wolves. And they don’t want wolves to be there, because they are really harmful to their way of life. I mean, there are so many of them, and they tend to not kill selectively like the tiger but they kill everything they find. The tiger will kill your dogs, or your horses maybe, but that’s only if the tiger is not able to hunt bigger prey because maybe she is old or she is injured or something like that. Wolves are really more harmful for them.

So, we could say: everything is related. For example, if lumberjacks came into the Primorsky and they chop down all the trees, it’s going to create a domino effect. The habitat of the tiger is going to be smaller and smaller, and the tiger will have to find another place. And probably this place will be full of humans – cities, villages, and so on. And if she’s not able to hunt, she will try to hunt everything she has to: dogs, humans, everything. There are the communities living there – well, they are not really living there, but surviving. Even now.

Why do you say the Udege are surviving, rather than living?

Because they live day to day. I mean, nature rules their daily life. In the summer they will pick fruit and during the winter they hunt. They collect sables, these small animals that are really valuable because of their pelts to make coats, but they don’t really get enough money to plan their life. I mean they get enough money to buy bullets, to buy vodka, to buy tea, to buy some other things, but it’s not really living but surviving from my point of view.

So are they still living the traditional hunter/gatherer way of life, or do they have some modernity?

Of course you find there mobile phones and tv, but their daily life is ruled by nature. During the winter they hunt, during the summer they collect. And that’s everything. During the summer it’s even worse in the taiga, because it is full of mosquitoes – and not the kind of mosquitoes you find in Spain, those are nice mosquitoes. These are a living hell. You have to go into the taiga covered, even your face, because they will eat you. I mean, I prefer being attacked by a tiger rather than being killed by thousands of mosquitoes. They’re like vampires!

How do the people relate to one another? Are they independent or have they formed a community?

They relate themselves, at least the Udege, in terms of families or clans. It’s not the kind of clans you can find in films, like Highlander with the MacLeods – I don’t mean the Vikings. They are families. They try to support each other. But, for example when they go hunting in the taiga, they can be there for one month up to three or six months, all on their own, so yes they get support from other hunters or gatherers. But yes, I would say when you are in the taiga, you must be really sure you can do it, because you will be on your own. Even if someone finds you in trouble, the distances are so big, you won’t be able to reach the city.

But they don’t hunt the tigers, even living under such conditions?

No, they don’t hunt the tigers. It’s prohibited.

What do they hunt?

They’re hunting elk, wild hogs, sables. Maybe they hunt other hunters… (laughs)

Ha! Um… Is that a joke…?

They hate poachers. Especially if these poachers came in from China, because this place is really close to the frontier of China, and in China it’s legal to hunt tigers, and they are really valuable. So, sometimes the poachers come and shoot the tiger but don’t kill them, and this is complicated because an injured tiger is even more dangerous.

You were describing why the Udege depend on tigers from a practical standpoint, but to what extent do they see it in terms of that practicality and to what extent is it more about the spiritual aspect?

It’s mixed. You have to consider the two biggest predators in this area: there is the tiger and there is the human. So they need to balance themselves. Sometimes, when I went hunting with them, they left some pieces of the animals behind for the tiger. I asked them, “Why did you do that? We have been chasing this animal for two days! Why not give it to me?” They told me the tiger is not considered a rival. “If I give some food to him, he will owe me a favour. And you never know when you’ll need a favour from a tiger.”

In the story that inspired you, there was the myth of ‘Amba’, the dark side of the tiger. And as Markov tried to kill a tiger, but failed, it released the curse of Amba. Do they still feel this way about killing tigers?

Yeah, you can call it a rule, you can call it whatever. When you’re inside the taiga, it’s silence. You don’t hear anything. Tigers are really good at hiding, so if you start a battle, probably you will lose it. Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but someone will pay for your mistakes. If you start shooting tigers, or trying to kill them, someone will pay.

For people living in the taiga, they can’t afford to stay in their homes like this, because they get their food in the taiga. If they can’t go out into the taiga because there is an injured tiger, they won’t find anything to eat. So, it’s best for them to share their space with this big predator and not get into quarrels.

So the idea is to treat them as an equal, and not compete.

Totally. Some of them have found themselves face to face with tiger, and they said: “I didn’t want to shoot her. So, I just shot into the air, and the tiger went away.”

And they devise these systems for co-existing with them, like leaving meat behind for the tiger.

It’s normal. And, for example, let’s say you are chasing an animal for two days, and you have managed to hunt a deer down in the middle of the taiga. It’s going to be like 20km from there to your home by skiing, so you have to take all this meat, maybe 250-300 kilos, on your own. So, you have to leave some pieces behind anyway. It’s also a matter of being smart: Even if I don’t want to leave it, I cannot carry everything on my own in one trip, so if I leave something over there, maybe the bears or the tigers will eat it and leave the other parts untouched for me.

So the hunters do try to come back for some of the meat that they leave behind?

Yeah. This is a funny part of hunting. Hunting and then coming back and then coming back and then coming back again.

You also included in your series some of the photos from the local cultural festivities around ‘Tiger Day’ there.

I found it interesting how culture and nature can be in the same level.

What else did you see that connected culture and nature?

Everything. First, you have to consider you need to follow the taiga rules to survive there. That makes it so that the way you behave in the taiga is going to define the way your culture develops.

I mean, if you don’t follow the rules, you probably won’t survive. This place has tigers, bears, wild hogs, snakes, mosquitoes – I mean, there are so many things that can kill you! Plus, drunk people.

Bears are also large predators, though. They don’t see the bears as equals?

I asked them about that. They told me the bear is easy to track down. He won’t hide from you. Even if there are fifty people, he will attack you. But the tiger? He will think twice, and he will find a way to surprise you, and hunt you down when nobody is watching.

So they respect that kind of thing. I mean, this is a smart animal that can think. It’s not about instinct. The tiger can think and premeditate these things. Tigers hunt by hiding, by surprise. There is a saying in the taiga that goes: If you see a tiger for one second, he has been watching you for one hour.

Yeah, that sounds threatening.

Yeah, he’ll be like: “Okay, maybe for breakfast, maybe for dinner…. Not really sure yet.”

While you were there photographing, you didn’t manage to see a tiger in the wild, right?

In the wild, no. And I think it’s a good thing. One night, I had my small hut, and I had a dog with me. And he began barking really loudly and wildly, and I said to him, “Okay, stop it, I want to sleep.” The next day, I realized there was a tiger like 50 meters away.

How did you know?

By the footprints. They were fresh – a few hours old. The tiger came over just to have a look and maybe to check out the new neighbours.

And you couldn’t perceive anything other than the dog barking?

No. I told the hunters about it, and they said, “This is normal – that’s why we have dogs.”

This interview with Álvaro Laiz was published on GUP Magazine. We talk about living in severe isolation, silent hunters and co-existing with predators.