"In a way you do have to turn off your higher faculties to engage with a baby—who has intense use for your creativity and resourcefulness and problem-solving skills, but who is not interested in what interests you intellectually."

—Julie Phillips (Milk Art Journal)

Stephen Shore: What Looking Looks Like

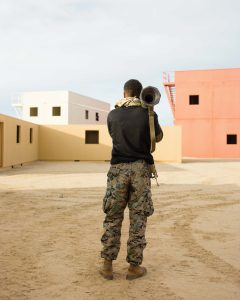

Few photographers have been as influential on the evolution of the art of photography as American photographer Stephen Shore (1947). In the ‘70s, when black and white was still considered the medium of ‘serious’ work, he was one of the frontier artists to use colour photography, and he continuously challenged the conventions of the medium at large by turning his camera towards ‘the everyday’ in direct subversion to the notion that photography had to prove itself a serious artform through pictorial or dogmatically formal means. Now, after more than fifty years of photographing, Shore alternates easily between large format film cameras and Instagram. A major retrospective of Shore’s photography has been developed as a travelling exhibition (at Huis Marseille in Amsterdam until Sept 4, 2016) and moves chronologically through the major projects of his life’s work. He speaks with us in this interview about artistic transparency, the wordlessness of visual language and responding to what you see in front of you.

One of your ongoing themes is ‘transparency’, in the sense that you deliberately want to exclude signs of your artistic workmanship in the photos. Was this always one of your goals or did this only emerge after you started to reflect on your work?

I would say it first appeared with the conceptual work (1969-70) and that by American Surfaces (1972-73) it was one of the main themes of the work. Let me explain the connection. I was interested in taking pictures that seemed ‘authentic’, that did not show as much the artifice of visual convention. In the conceptual work, I tried that through the idea of taking some of the artistic decisions out of my hands: I would follow a program, for example taking a picture at a set time, or from a set angle. I saw it as a way of subverting my imposition of visual convention. But, I ultimately was unsatisfied with that. I felt I ought to be able to do that really from the inside and to purge myself of it.

So, for American Surfaces, one of the things that I had in mind was to take a picture that felt less mediated by convention and so what I did was, whenever I thought of it during the day, I would take essentially a screenshot of my field of vision. I wanted to try to just see, ‘What does looking look like? What is the experience of seeing like?’ and use that as a reference for how to put a picture together.

Another way of looking at it might be, I think everyone’s had the experience that when they write, they tend to use a language that’s a little more formal and a little more stilted than when they speak, and I think there’s a visual equivalent to that. I wanted a picture that was more the visual equivalent of speaking.

You’ve also been teaching photography since 1982. Have any of your your students ever brought in some photographs looking down at the meal they just ate and asked, “But why doesn’t it work… you did it just like this?” What’s the best way to help a new artist understand why it worked for you, but it may never work again?

Well, none of them have exactly had the nerve to do that… but were they to do it, what I would say is one of the things I’m interested in is a kind of authenticity. it’s seeing the world with fewer filters. When I did it, that was the result of seeing the world with fewer filters. But, if you have in your mind my picture as a filter and have it as a model – “This is what a good picture should look like” – then even though the picture may look similar, your picture is the product of a filtered experience, and I suspect it will have a slightly different feeling. It won’t have the edge of immediacy, it won’t have the edge of discovery, because it really is plugging something you’re seeing into a model that’s already existing in your head.

I’m glad you bring up the ‘models’ you see the world through. In your book The Nature of Photographs (1998), which is a brilliant primer in how to view and understand the visual language of photography, you describe your own model as, “a complex, ongoing, spontaneous interaction of observation, understanding, imagination, and intention.” How do you apply that model in the moment?

I guess what I’m saying is that it’s not one thing, and it’s not something static. For example, Edward Weston wrote in the ‘20s or ‘30s about an idea of his called ‘pre-visioning’ where he imagines as he’s about to take the picture how the finished picture will look, and Ansel Adams called it ‘pre-visualization’. Other people try to make that sound like something dead – like you imagine the picture and then you simply fulfil it. I don’t want the model to sound static in that way, and if you read Edward Weston, what he’s talking about isn’t static, either.

I may approach a scene with certain questions in my mind or certain factors I’m working on that interest me, I may have certain ways of making a picture, but I also have to be responsive to what’s there. So, what I’m doing can wind up being different sometimes to what I intended going in, because the model changes in response to what I encounter.

“I may approach a scene with certain questions in my mind or certain factors I’m working on that interest me, I may have certain ways of making a picture, but I also have to be responsive to what’s there. So, what I’m doing can wind up being different sometimes to what I intended going in, because the model changes in response to what I encounter.”

Are you aware of the questions you’re trying to answer while in the moment?

It’s totally conscious. I may not put it into words because I’m thinking visually. For example, if you’re sitting at a desk now, and as you’re reaching over, you realize you’re about to knock over a glass of water and you grab it… there’s a lot of thinking that goes on without words in your head.

I’ve learned to be able to put what I’m doing into words because if I’m teaching, I have to communicate in words, but when I’m working I’m not thinking in words, I’m thinking visually. In visual terms, I’m consciously aware of issues that I’m working on or intentions that I have, almost all the time.

This is an excerpt. The full interview with Stephen Shore was published in GUP#50, the Hidden Gems issue, and also online at GUP Magazine. We talk about artistic transparency, the wordlessness of visual language and responding to what you see in front of you.